A month ago, when we were in the midst of a resurgence of international Black Lives Matter marches and activism, hearing calls for justice for George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and other victims of lethal police brutality, I dedicated the header of this site to a movement proposing solutions.

By now, you’ve probably heard of it. It’s called #8CantWait.

In a matter of days, many people (myself included) went from never having heard of #8CantWait, to spreading the word and making phone calls in support, to having (or being encourage to have) an intensely oppositional stance against it.

A month later, it likely feels like a distant memory, with half a dozen Rage du Jours punctuating the weeks since this was the issue. (Or at least felt that way for many of us.)

So to emphasize the part I want to emphasize, it’s the bouncing from one jarringly different position to the next in a matter of days – or, for some people, hours: people went from not knowing something exists, to loudly supporting it, to loudly discrediting it.

After showing an #8CantWait banner to hundreds of thousand of people on this site, I got a message via my contact page:

“You should know that [#8CantWait has] been proven false and the people who created it are actually funded by the police to discredit real abolition work that will make a real difference. At this point anything that isn’t focusing on abolishing the police is violence. You might as well put your knee on Geroge Floyds neck yourself. Support real abolitionists or get out of the way.”

I got another message the next day that said something similar:

“The Overton window has shifted so far that the majority of us are in favor of abolition. Stop peddling this reformist ‘#8CantWait’ bullshit we all know won’t work.”

My twitter feed was filled with similar sentiments and ideas. People retweeting threads attacking the policies advanced by the #8CantWait platform, or explaining why anything short of abolition isn’t enough. Sharing studies and articles about how reforms like implicit bias education and training don’t work.

It would have been easy for me to agree with the people who messaged me. In my tiny world, every voice felt like it was saying the same thing. I found myself thinking, “Maybe the Overton window has shifted.”

Maybe the time is ripe for abolition, and anything short of that is conservative, unhelpful, representing a step backwards, away from what everyone is demanding, not a small step in the right direction.

Phoning a (few hundred thousand) Friend(s)

I started to call and text friends to get their take on the current moment of focus.

I have friends who range from having been involved in the abolitionist movement for decades, to one who just recently marched for the first time for Black Lives Matter, so I thought I could get a representative-ish sample of what was on progressive people’s minds.

“What do you think of #8CantWait?” I asked a bunch of people.

And what I heard was several variations of “I support those policies, but they’re not enough,” with a sprinkling of, “Everyone is calling for defunding the police right now, so I think we should focus on that.”

The thing about the policies proposed in #8CantWait is that they’re compatible police abolition; they’re just baby steps, not a huge leap, but they would move us in that direction. This is something that even some of the most scathing, pro-abolitionist critiques of the campaign acknowledged.

It wasn’t that what was being asked for was harmful, it’s that it wasn’t alleviating enough harm. That’s a huge difference!

The response to the website banner pushing people to take action for #8CantWait was potentially confirming this attitude.

Only about 7% of the people who responded to the message with a click (instead of ignoring it, which roughly 99% of people did), clicked on the “Take Action” button. Everyone else hid the message.

Of the hundreds of thousands of people who saw that message about #8CantWait, seeing only a few hundred take action was confusing to me. After all, the vast majority of these people were on here that week to read tips for attending their first protest march, so I assumed they’d welcome that invitation to take action.

Because of the seemingly unanimous message I was receiving on Twitter, and the corroboration of that message from my close circle, I had the seemingly-reasonable thought: “Only 7% of people are wanting to take action for the #8CantWait platform because it’s not radical enough. I’m annoying hundreds of thousands of people with a conservative message, when they want something bolder. They want more.”

I took down the #8CantWait banner. I started looking for other ways I could help.

I don’t want to be part of the problem. The last thing I want to do right now is slow down progress from happening. The worst thing we could possibly do right now is squander this moment, and turn it into nothing.

The Poll and The Unexpected Graph

I decided that before I did anything else, I should do what I can to figure out what people actually believe, where they’re actually at. Before you can move someone anywhere, you need to know where they stand.

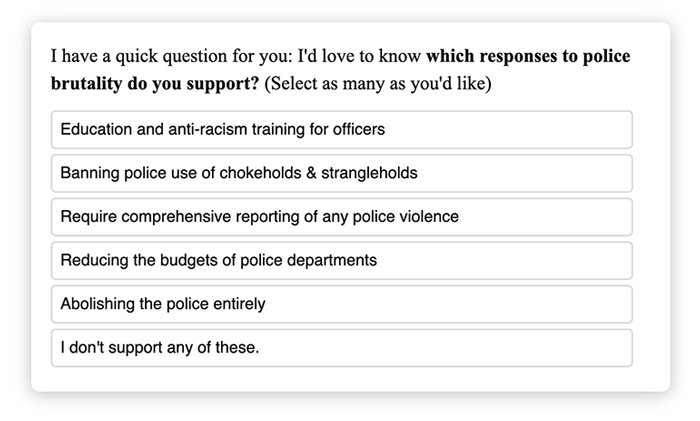

I worked up a simple poll for readers here, that would appear above every article for a couple of days, until I got enough responses to feel like the data I had were at least representative of IPM-goers, and hopefully most progressive, social-justice-activism-inclined people.

Here’s what it looked like:

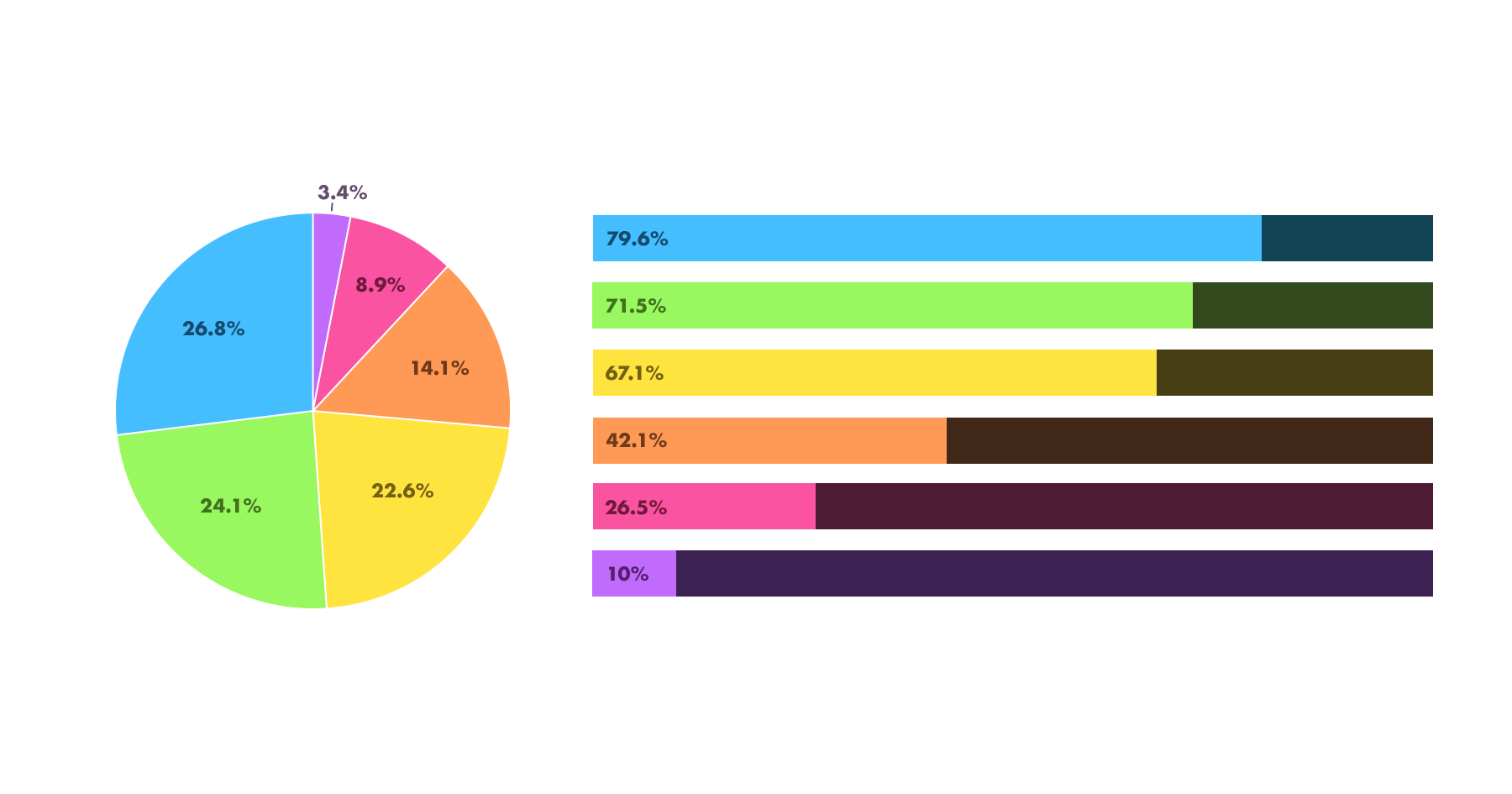

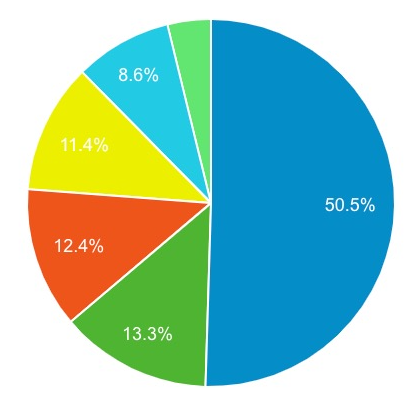

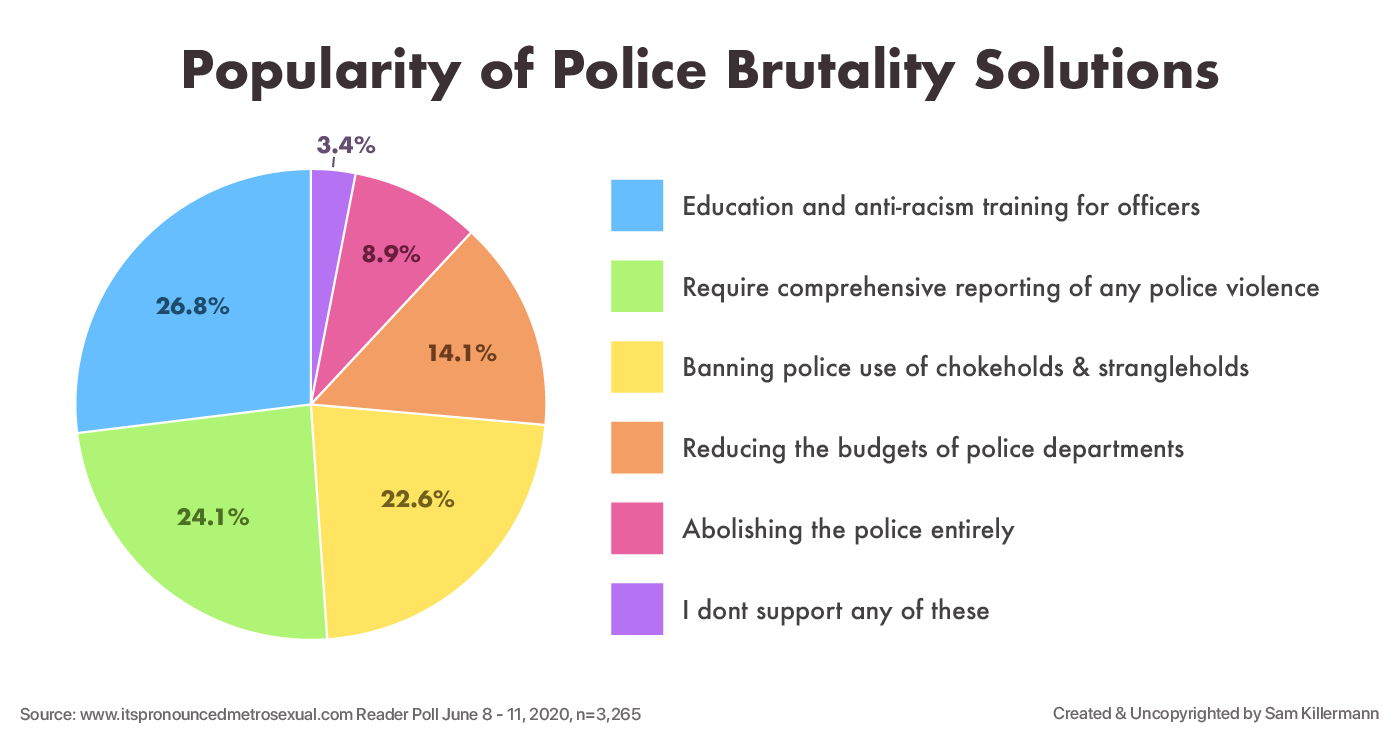

After a few hundred people responded, I checked the results to see which solution had received the most votes. Here’s what that looked like, as a pie chart:

Without the labels, and after hearing for the past days about nothing other than defunding the police, or abolishing them entirely, I assumed that the big blue wedge represented abolition, the big green one defunding, or vice versa.

I was gobsmacked twice when I looked at the legend:

First, I was shocked that education was the clear frontrunner. Second, I was shocked that I was shocked by that.

I shared the poll and pie chart screenshots with a few of the friends I had already been talking about all this with, who were familiar with IPM and what I generally write about here, the types of people this site is for. But I didn’t include the legend.

I asked, “Without the labels, which result do you think won?”

Every single person answered either “abolishing” or “defunding.” Every. Single. Person.

When I shared the legend they shared in my gobsmacking. The dozen or so responses can all be summed up by one of my friend’s reply of “WUTTTTT.”

Supported Solutions for Ending Police Brutality

I ended the poll when I collected more than enough results to draw conclusions, and to have a representative sample.

The main conclusion: we’re not going to be defunding the police any time soon. But I’ll get to that in a second. First, here’s the distribution of the votes for solutions to police brutality:

To fully grasp this, remember that people could vote for as many options as they wanted. So they weren’t limited by what’s “practical”, or having to choose a “realistic” solution over a pipe dream. They could choose both. But they did not.

The clear winning solution for police brutality was “education and anti-racism training for officers” with 26.8% of the total votes, while “abolishing the police entirely” got 8.9%.

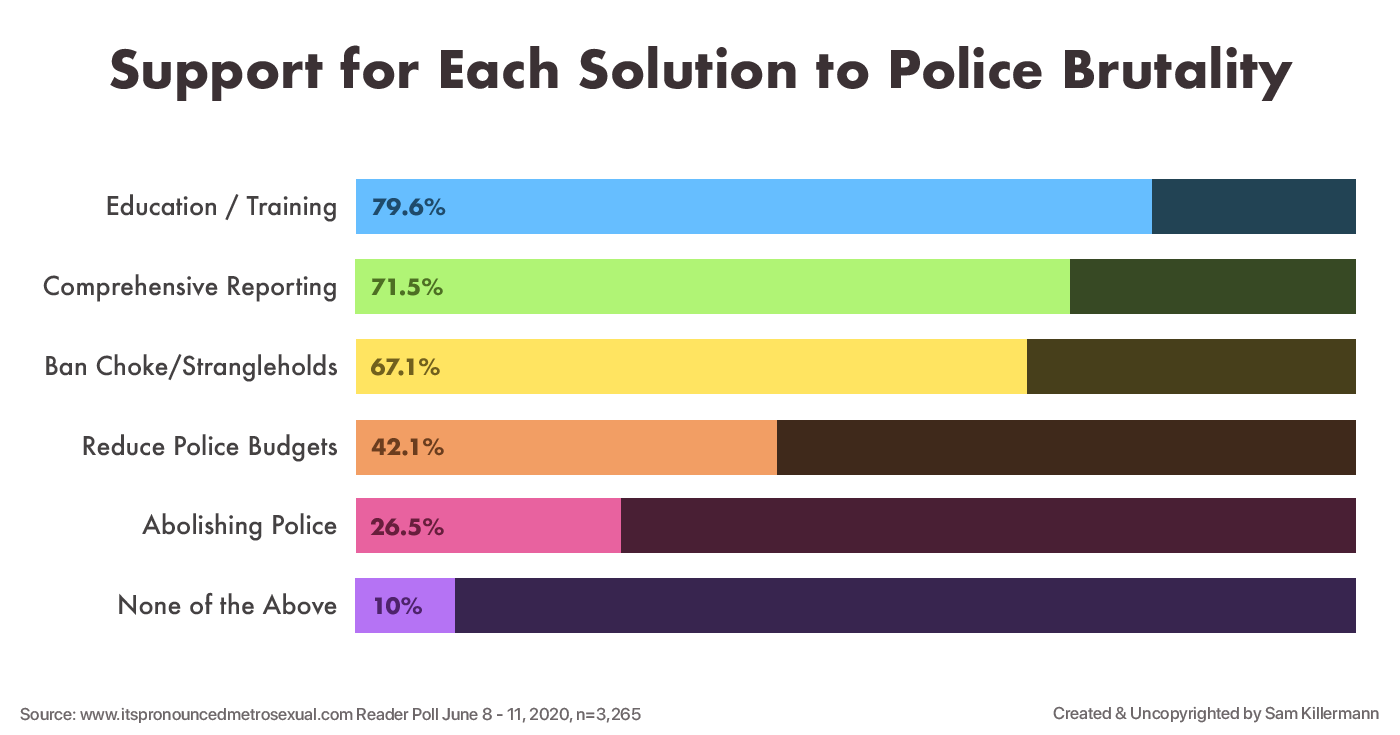

Here’s the breakdown of each solution, and the percentage of respondents who supported it:

An overwhelming majority supported education (79.6%), comprehensive reporting (71.5%), and banning chokeholds and strangleholds (67.1%). A minority supported reducing police budgets (42.1%), and an even smaller minority supported abolishing police (26.5%), while 10% supported none of these policies.

These data are from June 8 - 11, 2020. If there was a shifting of the Overton window that had happened because of the international protests, it would have been reflected in those numbers. But, instead, they line up fairly well with what we would have expected of progressive people prior to last week.

Considering these two graphs together, here are three things that are at the front of my mind:

- Anonymously, in a non-zero-sum game where every solution could have been supported, most people refrained from supporting the most radical (and loudest on progressive social media) policy.

- Meaning we don’t even have majority support of partial defunding or abolition within “our own people,” so we are up against a huge amount of pushback within left-of-center, center, and conservative-leaning people.

- Who the fuck are these 10% of IPM readers who don’t support any of these policies? Introduce yourself to me, please. I must know.

But above all else, my reaction to these data was “we have a massive problem on our hands.”

Two, actually. At least.

Two Huge Reasons We Won’t Defund the Police

To succeed in defunding the police, even locally, it will require buy-in from countless powerful institutions and figures. We’ll need a movement powerful enough to successfully topple an increasingly-powerful, increasingly-funded police force, which is supported by unions, lobbyists, military manufacturers, and huge swathes of citizens, politicians, industries, and small businesses alike.

But before we can do that, it appears we a lot of work to do in our own backyard, so to speak. Because this “we” I keep referring to isn’t much of a “we” at all. It’s a whole lot of “them,” we’ve just effectively shut a lot of them up.

I mean “us” up. We’ve shut us up.

1. We Don’t Actually Want To

“We” is a flexible word we use a lot (look at us go!). We might use it to mean “all of humanity,” or “Americans,” or “American voters,” or just “Democratic voters,” or even “very liberal Democratic voters.”

Each time we add a qualifier, we make a smaller “we.” Just in that list, we went from about 8 billion people, to about 300 million, to 130 million, to 65 million, to 10 million – a decrease of, if my math is right, about 99.9%. That’s a helluva smaller “we.”

The “we” I focus on here, generally, means “people who read this site and use these resources,” whom I hope are proponents of social justice, endeavoring to make our worlds more beautiful. If that’s you, you’re who I think about most, and try to tailor everything I do for. The “we” that makes up that “you” is smaller still, it’s a few million people – or .01% of the the biggest “we” above – a huge chunk of whom aren’t American, aren’t voters, and aren’t Democrats.

But who is the “we” we’re talking about when we’re discussing defunding police? One could assume we’re only talking about “we who support defunding the police,” in which case my heading above would be nonsense.

But it’s actually a trickier answer than it should be, because our ability to get an accurate sense of “we”, these days, is being hijacked.

Social Media Silos

When it comes to hot button issues like defunding the police, we don’t really know who we are.

Thanks to algorithmic siloing of social media (e.g., Facebook automatically showing you things it thinks you’ll like, or respond to, or click on) plus our own self-filtering (e.g., unfriending people who hold certain views, say certain “problematic” things, or don’t support the things we deem important), we’ve created social bubbles to occupy that are entirely unrepresentative of the world at large.

In times of global crisis, this filtering gets particularly pernicious.

When a global event is happening, it feels like everyone is reacting to it, and that’s more correct than not. But we only get to see our bubble’s reaction. This makes it easy for us to think, “Everyone is [insert emotion] about this right now,” when in reality what we should be thinking is, “Everyone in my tiny algorithmically and self-selectively filtered silo is [insert emotion] about this right now.”

Everyone in my tiny algorithmically and self-selectively filtered silo is furious about that cop killing that Black person.

With the current moment – where everyone is witnessing a resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement and an international uprising against police brutality – we went one step further: beyond just getting a read of what “everyone” is feeling, to what “everyone” thinks we should do about it.

A few days ago, one of my friends posted, “Unfriending anyone who says we should do anything other than defund the police.” Another friend posted, “If you are against abolishing the police you can’t say #BlackLivesMatter.”

Neither of these friends were people I had ever seen support anything abolition related in the past. As far as I knew, this was an opinion they recently formed, or they had been keeping their police abolition activism a secret previously.

Both got nothing but positive comments, likes, and shares. What wasn’t seen – and couldn’t be seen – was the people who didn’t react, who disagreed but didn’t want to say so, or who were tailoring their next post to live up to this new norm.

Plus Pluralistic Ignorance

Enter pluralistic ignorance, which is a cognitive bias where “a majority of group members privately reject a norm, but go along with it because they assume, incorrectly, that most others accept it.”

The silencing of dissenting opinions, often under the threat of social punishment or being ostracized, is all you need for pluralistic ignorance to thrive. We have that and more!

Adding to the active silencing of dissent, we have a passive lurker problem. In any social media space, the vast majority of people consume, while a tiny minority create and curate.

So most people aren’t posting, they’re just reading or signal boosting an already heavily-filtered feed. We can’t notice the passive lurking, and only notice the posts, likes, shares, and comments. If those all seem to be endorsing a view, and we’re not seeing many people dissent, it makes sense for us to think “that’s what everyone believes,” even if we are part of that everyone, and we don’t.

In response to me sharing the pie chart from my survey here, someone messaged me, “Wow. I genuinely thought it would be abolishing that was the most popular. I thought I was the only one who wasn’t onboard with that.”

I replied, “Have you commented that publicly?”

They replied, “lol of course not.”

2. We’re Asking the Wrong People for Permission

That subheading is going to piss a lot of you off. I know that, and I’m sorry. I didn’t write it because of that, but in spite of it: I just don’t know how else to sum up this idea.

And, I’m realizing now, this internal struggle I’m facing in writing this essay perfectly synopsizes the mess we’re in. As I wrote and rewrote that heading, and bounced between “permission” and other words (e.g., buy-in, support), I experienced the prickly problem in real time.

By “asking permission,” here, I simply mean the answer to, “Who has power to shape our activism?”

Imagine for a moment you’re a kid and you’re asking your parent for permission to play a video game. Do they need to love that idea, or support you spending several hours that way? No. Do you need their buy-in, or to convince them of the merits of gaming? Nope. You just need their permission. That’s the bar.

As social justice advocates, who are we asking for permission from, when we’re deciding what policies we support? What movements we back? What tactics or strategies to use? What shape our activism will take?

The second big reason we’re not going to defund the police is because we’re getting permission from the wrong people, and we’re altogether ignoring (at best) the people who make the rules.

We Seek Permission from “The Community”

Before we post something, or take a stance on an idea or proposal, or formulate an argument, we need a thumbs up from “The Community.”

In this case, a lot of things can stand in for what I mean by “The Community”: the social justice community broadly, the marginalized community experiencing oppression, or just our personal circle of social justice people.

What I mean in general by “The Community” is basically the subsection of people we see as already agreeing with us, the people “on our side."

Based on everything I said above regarding social media silos and pluralistic ignorance, some alarm bells might be ringing for you.

“How can we know if The Community gives us permission? Or supports a particular policy? Or doesn’t?” are all reasonable questions to be asking. It would be helpful if every statement of “THIS GROUP WANTS YOU TO DO THIS” was paired with blaring sirens.

But that’s not even the element of this disaster I want to draw you attention to here.

An equally siren-sounding issue is that The Community doesn’t actually make the rules.

We Also Need Permission from People with Power

We often oversimplify what we mean by “people with power” in social justice spaces.

I don’t mean “white people.” I do mean, at least, some white people. In particular, whatever percentage of white people – and all people – collectively have their hand on the lever of change.

I also don’t just mean people situated in roles of structural power (e.g., politicians, judges, principles, business owners). A lot of power is distributed to the many people who elect or hire or support those few. The voters who pick their District Attorney. The customers who choose to shop at that grocery store.

Here’s an inconvenient, but patently obvious truth: “our side” doesn’t currently have the power to make the change we want to make.

We’re not going to abolish the police because we are a tiny group (people supporting abolition) within an already small group (social justice people). If that weren’t true, and we had the power and numbers to enact the change we wanted, there’d be no police. Poof.

The people with power, in this case, are politicians, city council members, police chiefs, police unions, and – most importantly – all of the people who currently support policing (and the composition of this group will surprise a lot of social justice people: most Black americans, for example, support hiring more officers, in every poll or dataset I can find).

In order to defund the police – or enact any progressive, equitable, social-justice-oriented change – we need permission from people who aren’t “us.” We need “them.” Or we need a much bigger us. And ideally we get both.

Here’s another inconvenient truth: other than through violence, the only way to accomplish either of those goals, and in turn accomplish our goals, is going to be expanding the constituency we see ourselves as serving.

Without Both, We’re Doomed

“Who am I trying to make happy?” is a question we might find ourselves asking a lot in our lives, in different shapes:

- Who am I trying to impress?

- Who am I trying to convince?

- Whose feelings do I care about?

- Who do I want to support or help?

In social justice activism, particularly when it’s tinted with dogma, we are provided clear answers for all of these questions.

And often it’s via the exceptions that prove the rule:

We should not be trying to impress, convince, care about the feelings of, or support or help people who hold dominant group identities, who support oppressive policies, or who are in some way not onboard with social justice activism.

“If they say All Lives Matter, fuck ‘em,” to sum it up more gently than I see it characterized daily (blasé threats of violence are becoming all too common).

The “#AllLivesMatter crowd” is a way we’ve come to sum up everyone who isn’t supporting #BlackLivesMatter, which we’ve used (incorrectly, if the data are to be trusted) as shorthand for people supporting defunding.

But if we don’t let the people who aren’t already on our side shape our activism, if we don’t see them as part of our constituency – trying to impress or at least convince them, considering their feelings, finding ways to support and help them – we’re the ones who are fucked.

A Post Mortem In Progress

I almost published a version of this article on June 12th when the data were freshly collected. Then again a week after that. And now I’m writing it again, a month later. Why the delay?

Initially, I didn’t want to share those graphs, or any version of these observations in response to those data, if it would in any way take the wind out of the sails of the movement. I’d love to see us reach this destination. I’m firmly and happily aboard the ship.

Honestly, I wanted to be wrong. I was cautious not to share this, because I hoped in hindsight that I would have realized I had slowed us down in the name of caution.

Now it’s been a month, and all signs are pointing to the moment being squandered. To a movement derailed.

A lot of people have moved on to other activism, or new internet squabbles – the broader media surely seems to have called it a day on this. City budgets are coming out showing more funding for police, not departments being defunded (with a few exciting exceptions!). Even Biden, as presumptive Democratic nominee for president, announced he plans to increase police funding, and “definitively” does not support defunding the police.

With activists threatening to vote politicians out of office who don’t support abolition – or at least massive funding cuts, not more “reform” – I can’t help but wonder how comfy those politicians in question feel in the face of that threat.

I’m worried, with everything I just shared at the front of my mind, that politicians would be smitten with the idea of a popular vote on this issue, while we’re somehow thinking we could wield it do our smiting.

And this isn’t just about defunding the police. It’s about everything happening on a big stage in the social justice movement.

I’m hoping that by writing this now, and sharing it here, it can serve as the alarm bell you hear when you notice activism following the potentially doomed recipe above. Whether it’s activism focused on defunding the police (or reforming, which I know most of you support), or some other cause that catches the zeitgeist.

That said, this is not a post mortem yet. This is still a story in progress and we can change the ending. We just have to change just about everything.

But hey – what’s new? That’s what we signed up for, right?